The Witness

11/03/2016

The best part of The Witness is when you solve a puzzle that appears impossible - not just on first glace, but on long extensive glaces - 15 minute glances - 30 minute glaces - hour long forensic investigations. Puzzles that appear impossible because they stand alone in the world - no indication of how they might be solved, or even what their purpose might be in the grander scheme of things. With these puzzles all you know is that it does have an answer - and that the answer will be in the shape of a path through a maze.

Solving these puzzles requires a heightened sense of your surroundings - Sherlock-level observational skills - the ability to pick apart the smallest clues and develop it into a theory which can be verified.

Often these puzzles start the beginning of a chain of puzzles - cracking them is the eureka moment - Archimedes sitting in the bath, splashing water onto the floor in excitement. They bring a feeling that has been celebrated since the ancient Greeks - the joy of discovering a rule that governs the universe.

The rest of the chain of puzzles is what follows these eureka moments - a frenzy of mathematical investigation - exploration of the rule's implications, study of its behaviours, until you gain such a familiarity with the rule that you can't imagine not knowing how that aspect of the universe works.

And it does feel good - it feels great - to walk across the island and see the puzzles completed - their numbers dropping until just a few are left - just the final few secrets of the island, of the universe, remaining.

But all of this was what I'd paid for - the developer, Jon Blow, has a reputation that runs several miles ahead of him and has spoken many times about The Witness, about his game development philosophy, and these eureka moments he was trying to create. It is a game made for people like me - suckers for pretty graphics, programmers and scientific minds who enjoy puzzles, and who have the time and patience required for completing them.

More interesting were the things I'd not paid for, and not expected. Because about half way through the game I started slowly feeling quite negative toward it. I was feeling fatigued, distracted, angsty and I didn't think I could be bothered to finish it - but in the end I did, and I wasn't sure why.

It was the same kind of angst I felt as a teenager just before I quit competitive swimming - It wasn't that I wasn't enjoying myself, I just felt tired - weary of training several times a week, calling off social obligations, and sitting on the side of the pool for hours as the galas slowly passed by. But for several months I stuck it out, because I had a sense of lost investment - that the time I had already put into it was going to waste.

When I did finally quit I didn't feel bad. It was clear I was never going to be the greatest swimmer in the world. I wasn't any kind of child prodigy, and I had no other pressure to stay. Even so, I've often wondered how it must feel to really be one of these children - coached by parents from a young age - asked to forgo so many "normal kid" activities in delayed gratification. The ultimate sunk investment. I wondered what it might have been like if I'd stayed.

The question you always secretly want to ask those kids is "what happens if you fail?" "What happens if you don't make it?" "Isn't all of that time wasted?" And you know for some of them it will be - some of them wont make it. For some of them, they may already be able to see the end coming. They may already be miserable - bailing water - hoping to see the shore soon.

For some reason I always imagine these children being tennis prodigies. Perhaps it is because of the intense one-to-one nature of tennis. What happens when you find out you don't have the natural talent to be number one. How can you not take it personally? And then what is left other a dead end job?

So perhaps it was simply this that helped me finish - fear of lost investment. Just like tennis, The Witness is a very individualistic game, which means it seems like a personal failing to quit - there is always a natural resistance to this.

This isn't the only way in which The Witness is like tennis.

There are roughly there are two types of games in this world - score based games and skill based games. In score based games progress is measured by the strength of your virtual character. By sinking time into the game your virtual power grows - you gain new virtual skills or you literally gain "experience points" that power you up.

These games are fun because virtual characters can do a whole number of things you yourself can't do. I couldn't really own a snorlax or cast magic - but I can in video games.

And then there are skill based games - in these games your virtual character often remains pretty much the same. Instead progress is measured by you getting stronger. You become better at the game - you gain new skills and techniques. The experience points are real.

Tennis, like most real life sports, is like this. Many computer games are too - Call of Duty, Fifa, and of course The Witness. In these games the rules never change - the world doesn't change - and your avatar remains the same. It is only you who can improve to progress.

In a way these games offer something deeper than score based games because they improve you as a real person - they can make you stronger, smarter, quicker in real life. Score based games ask for your time, and in return give you a bigger number, or a prettier image, but skill based games ask for your time and give you a real life return on your investment - they improve you as a person.

In The Witness there are no score based rewards - no big numbers you can increase, and no virtual golden trophies or power-ups for completing puzzles. At the end of the game you have exactly the same powers and score you started with. The reward for completing puzzles is simply more puzzles - more puzzles and harder puzzles.

Then Jon Blow is like your tennis coach - and the puzzles are a series of opponents. Relentlessly designed and ordered by Blow to create the perfect series of matches to train you up. And because Jon Blow is one of the world's greatest designers of puzzle games in the world, paying $50 for The Witness is like paying $50 for Rafael Nadal to teach you tennis.

Except that it isn't.

Because The Witness isn't tennis. It wont make you famous, or rich, or renowned. And Jon Blow isn't Rafael Nadal - because he doesn't fly first class, and your mum probably doesn't fancy him. So actually it's more like being coached in "Stephen's Sausage" puzzles by an obsessive computer programmer for 20 to 30 hours - which at $50 suddenly doesn't sound like such a great deal.

The reality is no one does anything fueled on personal improvement and delayed gratification alone. We're all interested in some end goal although exactly what that is isn't always clear.

This is why when I quit swimming no one blinked an eye. It didn't matter that swimming was making me stronger, fitter, and more healthy - that it was improving my real life. It was completely reasonable that all I really wanted to do was go out and get drunk with the rest of my friends - the non-gaming equivalent of racking up hours and hours on Pokemon.

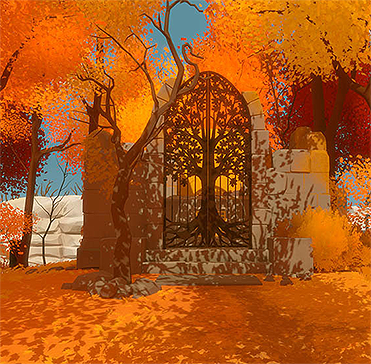

Not even a game like The Witness can function entirely separately from this fact - no matter how hard it tries. Yes - there aren't any golden trophies or fireworks going off when a puzzle is completed - but there are plenty of little gamified tweaks around aimed to keep you engaged. The sound design is careful and pleasing - with little pings of gratification when puzzles are completed, and the comforting crunch of leaves as you walk around. The controls are weighty and satisfying, and of course there is the painstakingly hand crafted, and absolutely beautiful island upon which the whole game is set. These weren't afterthoughts - thousands of hours of development went into these things. There is no chance that Jon Blow doesn't understand this aspect of human nature.

It's just that sometimes The Witness just feels so incredibly strict - like it wants you give you just enough reward to allow you make it around the island and finish the game, but no more - no silly fun along the way. Would giving the player a little more reward really be such a problem? I don't think so. And many reviewers are certain they know why the game was designed to be so strict - it's because Jon Blow is "pretentious".

Some elements of this criticism are unavoidable, but curiously a lot of the things which typically come of as pretentiousness don't actually really apply to The Witness. For example, many common criticisms of modern art just don't work - The Witness isn't unoriginal, it isn't particularly contrarian, it certainly isn't overly simplistic, and a child probably couldn't have made it. Not to mention, that for anyone talking about games being "pretentious" it is probably a little late re: pot-kettle-black (or really for anyone who when asked what a game is about replies with anything other than a one word answer - football, space, shooting, pirates, monsters, jumping).

But there is a definite feeling that The Witness was trying to give the illusion of deeper meaning without actually really having any. It seems to me it just doesn't have any and expectations were too high. After all, The Witness did spend eight years in development so people can be forgiven for expecting a lot. It is natural to feel like you are missing something if you are playing a puzzle game which everyone has raved about, and really can't see any deeper meaning. But it probably just never existed in the first place. For me, and many other critics, even just the appearance of deeper meaning is still a success.

The Scottish comedian Billy Connolly put it best - he said that when he sits down in a pub, looks over to the bar, and sees some guy telling a story to his friend, and the friend is laughing his head off, he sees all he aspires for in his professional career. That is - all he wants is to get up on stage and try to be as funny as a normal guy, in a normal pub, telling a normal story to his normal friend.

The thing is - being deep, and genuine, and convincing isn't always possible. Sometimes an imitation is the closest you can get. Just because you didn't laugh your head off with The Witness, doesn't mean you missed the punchline, and doesn't mean the comedian sucks.

But there is also a feeling that somehow The Witness is very self involved - that it is a vanity project intended to make Jon Blow look very smart and everyone else look very stupid. I can see where this is coming from - there is certainly a lack of generosity in some parts of The Witness.

I don't mean literally that the game is selfish, but more the idea that The Witness does not give away its content easily. There is an idea in art that one should show what they've made, and the ideas they've had, in the most straight forward way which demands the least from the consumer. This is often referred to as generosity and the goal is to maximise what the consumer gets from the artwork - the meaning, enjoyment, fulfillment - while minimising the obstacles that the consumer has to navigate to get that reward, and the investment they have to make.

This idea is popular in writing. It is why you should avoid obfuscated text and purple prose unless it really adds to the story, and why you should edit out any sections which the reader wont get anything from. It also explains why it is important to articulate your ideas clearly - it is what distinguishes you from those who hide the fact they have nothing interesting to say behind impossible to decipher text. If what you have to say is clear no one can say it isn't there. A generous artist is an artist that makes incredible artwork anyone can appreciate.

And just like books, or paintings, games can be generous too. A generous game gives the player the maximum reward with the minimum investment. It means having depth without a steep learning curve, and explaining mechanics in the most understandable way. It means no artificial barriers to enjoyment - no unnecessary unlockables, and of course no pay-to-win.

This idea of generosity, people will tell you, it why there is no text or instructions in The Witness. Because it is more generous to show the player how a game mechanic works than to ask them to spend the time reading a bunch of text - to simply and effectively show how a game mechanic works should take less time, investment, brainpower from the player, and give a greater reward.

To some extend this is true - but The Witness takes this too far. Playing The Witness there were many times when I got five or six puzzles deep into a chain of puzzles only to realise I didn't understand the mechanic I was meant to be using. This was an incredibly frustrating feeling and it wasn't my fault. I felt cheated, because although the maze puzzles appear simple, they often have unexpected behaviour and unexplained edge cases, and the reality is there is no way to fully explain all these the mechanics in just a few puzzles. Sometimes you are forced to just guess how some things work - trying multiple combinations until something fits. That isn't generous any more - the generous thing would have been to just state the mechanic up front clearly and easily, and if that has to be in text then so be it.

The Witness doesn't lack text for generous reasons. It does so because it is romantic - because to designers is an appealing and interesting goal to try and create a game which uses no text at all. Even if the end result is a less rewarding and more frustrating game, there is an argument that this is still just somehow better.

This really reveals a lot about The Witness, because the artistic aspect of The Witness is not very generous either. While sometimes it states things fairly clearly, the story of the island is still a complete unknown, and the more general philosophy is scattered across the island and divided into a number of disconnected video and audio snippets which only loosely tie together. As with the lack of text, there is no practical reason why the message of The Witness couldn't have been made clearer. It does not add to the reward of the game to have the message so abstract. Many beautiful artworks have been created which are not unnecessarily unclear and The Witness could have been one of them.

No - the reason The Witness contains no text, no story, and no clear philosophy is entirely for romantic reasons. Because there is something romantic about a silent protagonist walking around an island filled text-less puzzles and stone statues, lost audio recordings and beautiful scenery. Just like there is romance in building a game like The Witness, over eight years of time in a small indie studio.

And thank god there is - because romance is what ultimately drives people to finish things. Sunk investment has nothing on romance - romance gets people up in the morning, it drives them through their frustrations. Romance is what makes people solve problems that on first glance, on second glance, on years of investigation, appear impossible. For a tennis player romance might be sports cars and fame - but for a programmer romance is walking around a deserted island solving puzzles in silence - building the game they've always dreamed of making.