New Movement Model

07/01/2026

Recently on the Unreal Engine team I had the chance to work with Caleb Longmire and Jack Potter on a new preset movement model for locomotion - integrated into Mover as a more up-to-date replacement to the very old default Walking Mode of the Character Movement Component which as far as I know dates back to the Unreal Tournament days.

It was a very fun little R&D project, and if you grab the 5.7 release you can take a look at what we came up with. Everything mentioned here is already integrated into Mover as the new "Smooth Walking Mode" which is used in the latest release of the Game Animation Sample Project. We'd be interested to hear any feedback you might have as we'd like to really take this opportunity to provide the best preset we possibly can.

We had a few goals in developing this new movement model:

- It should be much easier to understand than the old Walking Mode of the Character Movement Component. It should be possible for designers and programmers to have a clear mental model of what each parameter is doing.

- It should be able to produce a large range of movement behaviours - from emulating the old Walking Mode, to spring-based movement, and more.

- It should not require complex dynamic parameter adjustment at runtime to achieve what a designer wants from the character movement.

- It should be capable of producing realistic movement profiles that reflect how people really move.

That's quite a lot of goals to achieve, but I think in the end we managed to come up with something that does pretty well for most of them. I've put together a little web-demo which re-implements all the core logic which you can have a play around with here and find the source code to here.

But although I think we achieved our goals relatively well - as you can see - there are still quite a lot of parameters to this movement model. So let's break it down a bit and go through our thought process while it was being developed.

At its most basic, our movement model takes as input a desired velocity, and adjusts the current velocity towards it using a constant acceleration/deceleration:

struct movementstate

{

vec2 pos; // position

vec2 vel; // velocity

};

struct movementparams

{

float acceleration = 700.0f; // pixels/second^2

float deceleration = 900.0f; // pixels/second^2

};

void update_movement(

movementstate& state,

vec2 desired_vel,

float dt,

const movementparams& params)

{

// Compute the velocity difference between the current and target

vec2 vel_diff = desired_vel - state.vel;

// Check if we are meant to be accelerating or decelerating

bool is_accelerating = length(desired_vel) + 1e-4f > length(state.vel);

// Compute the desired acceleration magnitude

float acc_mag = is_accelerating ? params.acceleration : params.deceleration;

// Compute minimum acceleration required to take us toward target velocity

vec2 acc = length(vel_diff) < acc_mag * dt ?

vel_diff / dt : acc_mag * normalize(vel_diff);

// Integrate acceleration to update velocity

state.vel = state.vel + dt * acc;

// Integrate velocity to update position

state.pos = state.pos + dt * state.vel;

}

That gives movement which looks like this.

This is kind of the most basic way to set up character movement. But interestingly, this isn't actually how the default Character Movement Component Walking Mode in UE works.

I'm simplifying things a bit, but basically the way the default Character Movement Component Walking Mode works is this: if you request a speed slower than the current speed it decelerates as normal using a constant deceleration towards that lower speed. If you request a speed faster than or equal to your current speed it adds some proportion of your desired velocity to your current velocity then clamps the magnitude of the result.

We can actually interpolate between these two different ways of doing things like this:

struct movementparams

{

float acceleration = 700.0f; // pixels/second^2

float deceleration = 900.0f; // pixels/second^2

float directional_acceleration = 0.0f; // if to apply acceleration directionally

};

void update_movement(

movementstate& state,

vec2 desired_vel,

float dt,

const movementparams& params)

{

// Get the previous velocity magnitude

float prev_vel_mag = length(state.vel);

// Compute the velocity difference between the current and target

vec2 vel_diff = desired_vel - state.vel;

// Check if we are meant to be accelerating or decelerating

bool is_accelerating = length(desired_vel) + 1e-4f > length(state.vel);

// Compute acceleration magnitudes

float lateral_acc_mag = is_accelerating ? (1.0f - params.directional_acceleration) *

params.acceleration : params.deceleration;

float directional_acc_mag = is_accelerating ? params.directional_acceleration *

params.acceleration : 0.0f;

// Compute lateral acceleration

vec2 lateral_acc = length(vel_diff) < lateral_acc_mag * dt ?

vel_diff / dt : lateral_acc_mag * normalize(vel_diff);

// Compute directional acceleration

vec2 directional_acc = length(desired_vel) > 1e-8f ?

directional_acc_mag * normalize(desired_vel) : vec2();

// Find the combined acceleration

vec2 acc = lateral_acc + directional_acc;

// Integrate acceleration to update velocity

state.vel = dot(vel_diff, acc * dt) < dot(vel_diff, vel_diff) ?

state.vel + dt * acc : desired_vel;

// Clamp the velocity magnitude to the max of the desired velocity and the previous

float max_vel_mag = max(prev_vel_mag, length(desired_vel));

state.vel = length(state.vel) > max_vel_mag ?

normalize(state.vel, 1e-8f) * max_vel_mag : state.vel;

// Integrate velocity to update position

state.pos = state.pos + dt * state.vel;

}

Here, the directional_acceleration parameter allows us to switch between the two modes - simple constant acceleration/deceleration and the way the Character Movement Component walking mode does it:

As you can see, high "directional acceleration" gives us movement with a bit more slide or drift, and also allows the character to change direction to some degree without losing speed. Very roughly I like to think of low "directional acceleration" movement as being like a quad-copter, and high "directional acceleration" movement as being more like a swamp airboat.

The final limitation of this model is in turning. When using basic acceleration/deceleration it's impossible to make turns without slowing down while when using directional acceleration it's difficult to get sharp turns without making the acceleration too strong.

To allow designers to tweak the character's ability to turn without losing speed we can add a "turn strength" parameter - which is used to control a damper that directly pulls the current velocity direction towards the desired velocity direction:

struct movementparams

{

float acceleration = 700.0f; // pixels/second^2

float deceleration = 900.0f; // pixels/second^2

float directional_acceleration = 0.0f; // if to apply acceleration directionally

float turn_strength = 0.0f;

};

void update_movement(

movementstate& state,

vec2 desired_vel,

float dt,

const movementparams& params)

{

// Pull the velocity direction toward the desired velocity direction

if (params.turn_strength > 1e-8f && length(desired_vel) > 1e-8f)

{

state.vel = damper_exact(

state.vel,

length(state.vel) * normalize(desired_vel),

1.0f / params.turn_strength,

dt);

}

// Get the previous velocity magnitude

float prev_vel_mag = length(state.vel);

...

This allows us to, if we want, make the character turn without losing too much velocity.

At this point we can emulate relatively closely the behaviour of the Character Movement Component Walking Mode but with a simplified set of parameters.

But is this actually a good thing? I've played a lot of Unreal Tournament and although it's one of my all-time favourite games, and the movement is incredibly fun, I don't think anyone would try to claim that the movement is realistic. How do humans actually move? And what additions do we need to make to this model to allow it to emulate those movements?

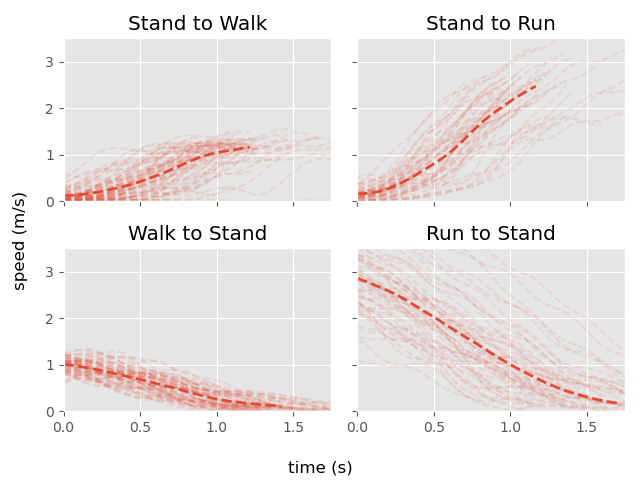

As usual - I like to approach this question from a data-driven viewpoint. Let's examine the velocity and acceleration profiles of some actual motion capture data and see what it looks like. Here I've plotted the velocity and acceleration of a whole bunch of start and stop mocap clips as well as the average:

Unfortunately, it is hard to derive too much from this data. As you can see, there is a lot of variance, and the fact that this movement has already been smoothed adds some kind of bias. But to me at least, it looks like the rough shape is this: for acceleration there is a ramp up that looks somewhat like a spring damper, and for deceleration there is ramp down that is a bit more linear but still with a small lead-in and lead-out.

That doesn't match our current velocity profiles, which are too linear and are not smooth enough. To fix this we can put our velocities through a spring. And in particular we can use a velocity spring, which tracks the target at some fixed time in the future to make sure it does not lag behind.

So that is what we are going to do - we're going to take everything we've made so far and use it as the target for a spring, which we will try to track ahead by some amount of time to prevent lagging behind.

struct movementparams

{

float acceleration = 700.0f; // pixels/second^2

float deceleration = 900.0f; // pixels/second^2

float directional_acceleration = 0.0f; // if to apply acceleration directionally

float turn_strength = 0.0f;

float acceleration_halflife = 0.0f;

float deceleration_halflife = 0.0f;

float acceleration_compensation = 0.0f;

float deceleration_compensation = 0.0f;

};

struct movementstate

{

vec2 pos; // position

vec2 vel; // velocity

vec2 acc; // acceleration

vec2 vel_imm; // intermediate velocity

};

void update_movement(

movementstate& state,

vec2 desired_vel,

float dt,

const movementparams& params)

{

// Pull the velocity direction toward the desired velocity direction

if (params.turn_strength > 1e-8f && length(desired_vel) > 1e-8f)

{

state.vel_imm = damper_exact(

state.vel_imm,

length(state.vel_imm) * normalize(desired_vel),

1.0f / params.turn_strength,

dt);

}

// Compute the velocity difference between the current and target

vec2 vel_diff = desired_vel - state.vel_imm;

// Check if we are meant to be accelerating or decelerating

bool is_accelerating = length(desired_vel) + 1e-4f > length(state.vel_imm);

// Compute acceleration magnitudes

float lateral_acc_mag = is_accelerating ? (1.0f - params.directional_acceleration) *

params.acceleration : params.deceleration;

float directional_acc_mag = is_accelerating ? params.directional_acceleration *

params.acceleration : 0.0f;

// Compute lateral acceleration

vec2 lateral_acc = length(vel_diff) < lateral_acc_mag * dt ?

vel_diff / dt : lateral_acc_mag * normalize(vel_diff);

// Compute directional acceleration

vec2 directional_acc = length(desired_vel) > 1e-8f ?

directional_acc_mag * normalize(desired_vel) : vec2();

// Find the combined acceleration

vec2 acc = lateral_acc + directional_acc;

// Velocity half-life and compensation

float vel_halflife = is_accelerating ?

params.acceleration_halflife : params.deceleration_halflife;

float compensation = is_accelerating ?

params.acceleration_compensation : params.deceleration_compensation;

// Find the time to track into the future

float lag = dt + compensation * halflife_to_lag(vel_halflife);

// Compute the next velocity plus the tracking velocity

vec2 next_vel = dot(vel_diff, acc * dt) < dot(vel_diff, vel_diff) ?

state.vel_imm + dt * acc : desired_vel;

vec2 track_vel = dot(vel_diff, acc * lag) < dot(vel_diff, vel_diff) ?

state.vel_imm + lag * acc : desired_vel;

// Clamp the velocity magnitude to the max of the desired velocity and the previous

float max_vel_mag = max(length(state.vel_imm), length(desired_vel));

next_vel = length(next_vel) > max_vel_mag ?

normalize(next_vel, 1e-8f) * max_vel_mag : next_vel;

track_vel = length(track_vel) > max_vel_mag ?

normalize(track_vel, 1e-8f) * max_vel_mag : track_vel;

// Update the actual velocity

simple_spring_damper_exact(state.vel, state.acc, next_vel, vel_halflife, dt);

// Update the intermediate velocity

state.vel_imm = next_vel;

// Integrate velocity to update position

state.pos = state.pos + dt * state.vel;

}

If we provide separate half-life and apprehension controls for this spring during both acceleration and deceleration, we can get some profiles that look pretty similar to the real motion capture data:

Here you can see the un-smoothed intermediate target shown in orange.

If we make our acceleration and deceleration values very large so that they snap to the target velocity, we effectively end up emulating a spring-based movement model:

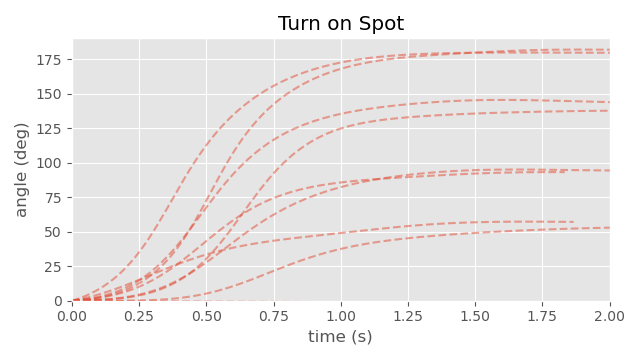

The final piece of our model is modelling the character rotation. In this case we entirely separate the rotation from the position/velocity. If we look at some motion capture data again we can see that the character rotation tends to follow an S-shape - and seems to take about the same amount of time no matter how many degrees the character is turning by:

A pretty good fit for this style of movement is a double spring - so this is what we use to model the change in rotation:

struct movementstate

{

vec2 pos; // position

vec2 vel; // velocity

vec2 acc; // acceleration

vec2 vel_imm; // intermediate velocity

float rot = 0.0f; // rotation

float ang = 0.0f; // angular velocity

float rot_imm = 0.0; // intermediate rotation

float ang_imm = 0.0; // intermediate angular velocity

};

struct movementparams

{

float acceleration = 800.0f; // pixels/second^2

float deceleration = 1400.0f; // pixels/second^2

float directional_acceleration = 0.0f; // if to apply acceleration directionally

float turn_strength = 1.0f;

float acceleration_halflife = 0.1f;

float deceleration_halflife = 0.05f;

float acceleration_compensation = 1.0f;

float deceleration_compensation = 0.0f;

float rotation_halflife = 0.15f;

bool rotation_double_spring = true;

};

...

// Integrate velocity to update position

state.pos = state.pos + dt * state.vel;

// Update Rotation either using double or single spring

if (params.rotation_double_spring)

{

double_spring_damper_angle(

state.rot, state.ang,

state.rot_imm, state.ang_imm,

desired_rot,

params.rotation_halflife,

dt);

}

else

{

simple_spring_damper_angle(

state.rot, state.ang,

desired_rot,

params.rotation_halflife,

dt);

}

}

Putting it all together gives us the model from right at the beginning of the article. And now I hope you can see how powerful and diverse a model this can be. We can produce very realistic looking profiles or we can produce very fun, responsive, gamey style movement.

In particular, by breaking down and simplifying the behavior of the existing Walking Mode provided by the Character Movement Component, our new mode can express a much wider range of behaviours using a more minimal and intuitive set of parameters that don't require runtime adjustments - that includes both realistic and arcade style movement.

Appendex

Maybe some closing notes on this movement model.

First of all - this model is in no way delta-time invariant - and should be sub-stepped if you want accurate results for larger timesteps.

Second, there is no real physical interpretation of this model. Both "directional acceleration" and the "turn strength" features I don't think have any real meaningful parallel in the real world. This is not necessarily a problem. Games are not the real world, and often need to fake things for various reasons. But you still might need to be careful if your movement model interacts with the physics engine as both of these features can produce large spikes in acceleration as they allow the character to change direction very quickly - and this involves large amounts of force being applied to the character.

The use of the spring can mean that the character might take a long time to actually reach a velocity of exactly zero during stops (and reach the exact target velocity during movement) so you might want to add an epsilon and clamp to exactly the target when within some threshold.

Finally, you need to be careful when you include external forces into this model such as collisions, pushes, or moving platforms since those need to affect both the velocity of the character itself but also the intermediate velocity of the velocity spring.

So that's about it. I hope this has been an insightful article, and as always thanks for reading.